Niamh O'Malley

Placeholder

26 February - 30 May 2020

I see no Spanish ships…

‘P’ for placeholder: Once again we find ourselves in the interesting position of writing an exhibition text without specific knowledge of the exact works, of how they will look or configure in the show. So in essence, not only is ‘placeholder’ the title of the show, but it is technically the purpose of this short essay. This of course does not mean that it is an inferior surrogate, rather language floated into a parallel space. Bear with me, I will develop… In an earlier life as a gallery technician I was working on an extensive museum installation, and number of works; a Picasso, Léger and a Mondrian etc., were all indicated in their place within the hang by postcard reproductions. Thirty years later, I find that I vividly remember the visual of the small card reproductions taped to the wall, and curiously not-so-much the actual paintings. There goes Greenberg’s theory of auratic presence, and one up for Walter Benjamin on reprographics, I guess it just depends what situates first in the muscle memory of experience.

In linguistics, a placeholder is “a person or thing that occupies the position of another person or thing” [i]. Notionally; an ‘element’ in a sentence that is required by syntactic constraint, yet carries little-or-no semantic information or evidenciation, and thus serves as a purposeful deflection of intent. For example, the word ‘it’ becomes a subject in the hypothetical sentence; it is a pity that they left, whereas the underlying subject/agenda is; that they left at all from ‘wherever’, for whatever, unspecified but apparently disappointing reason. The strategic employment of the placeholder thus creates space into which to dream or project, dematerialising otherness; an imagined landscape of immanence, or equally, negation. Everything and nothing. I see no Spanish ships.

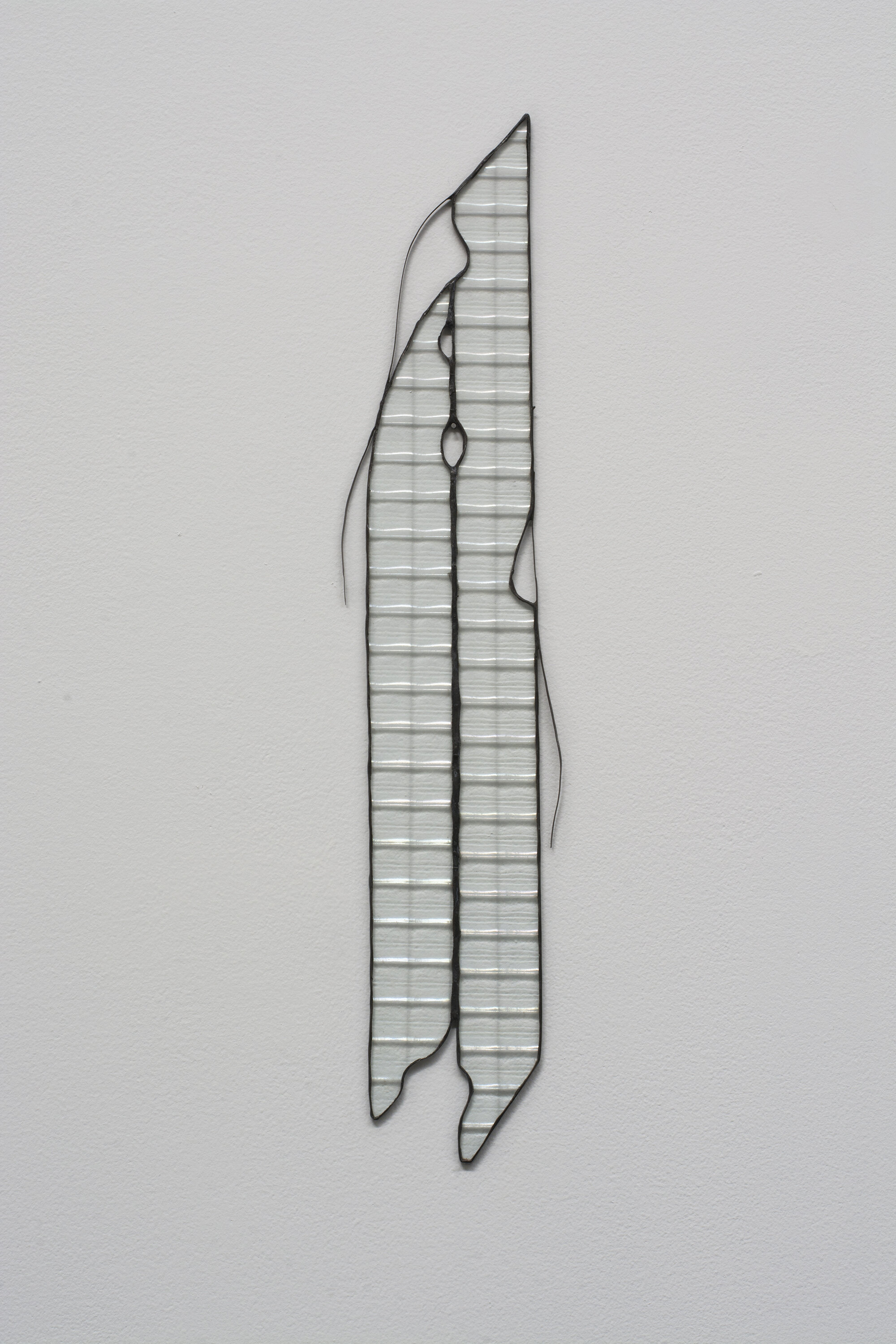

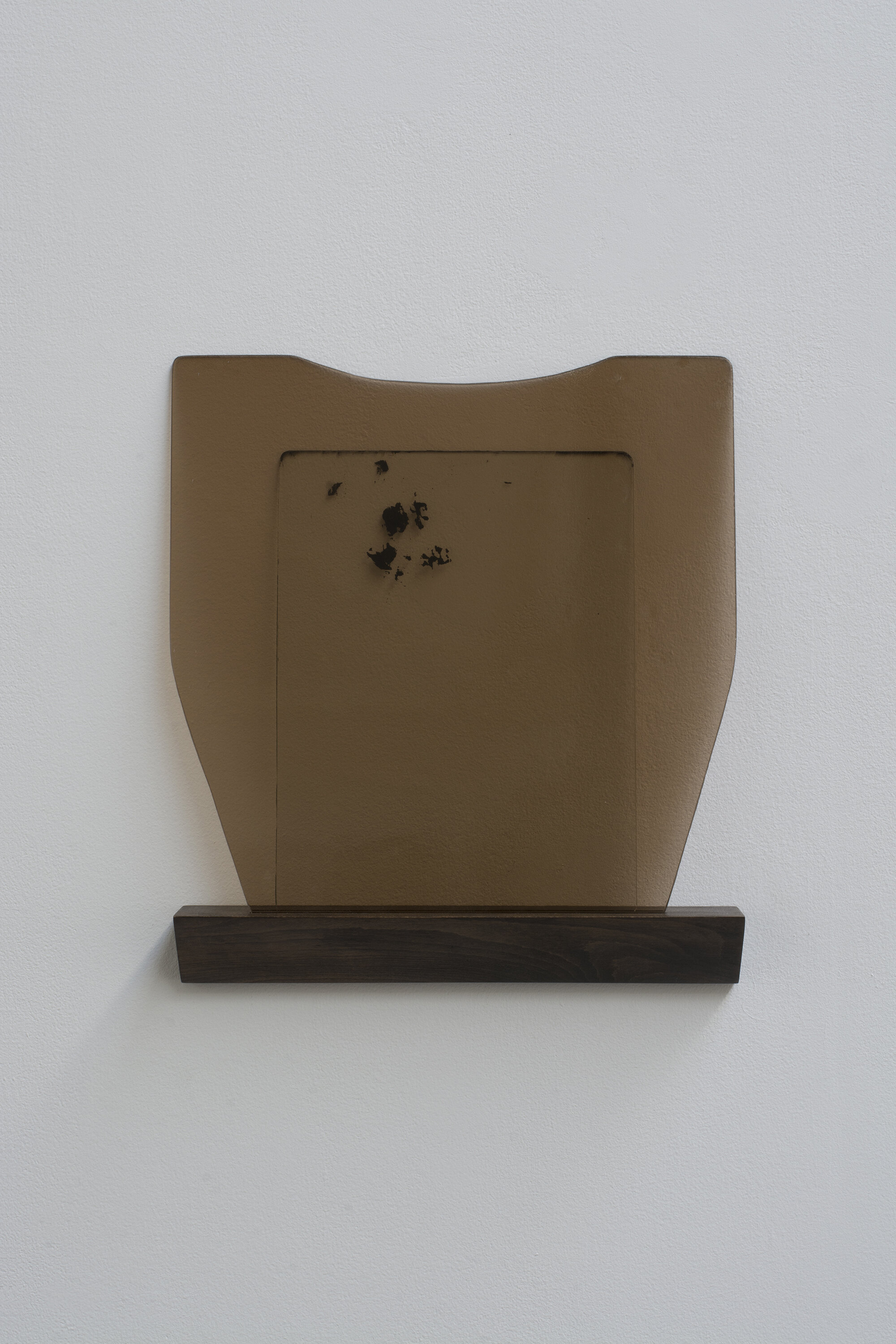

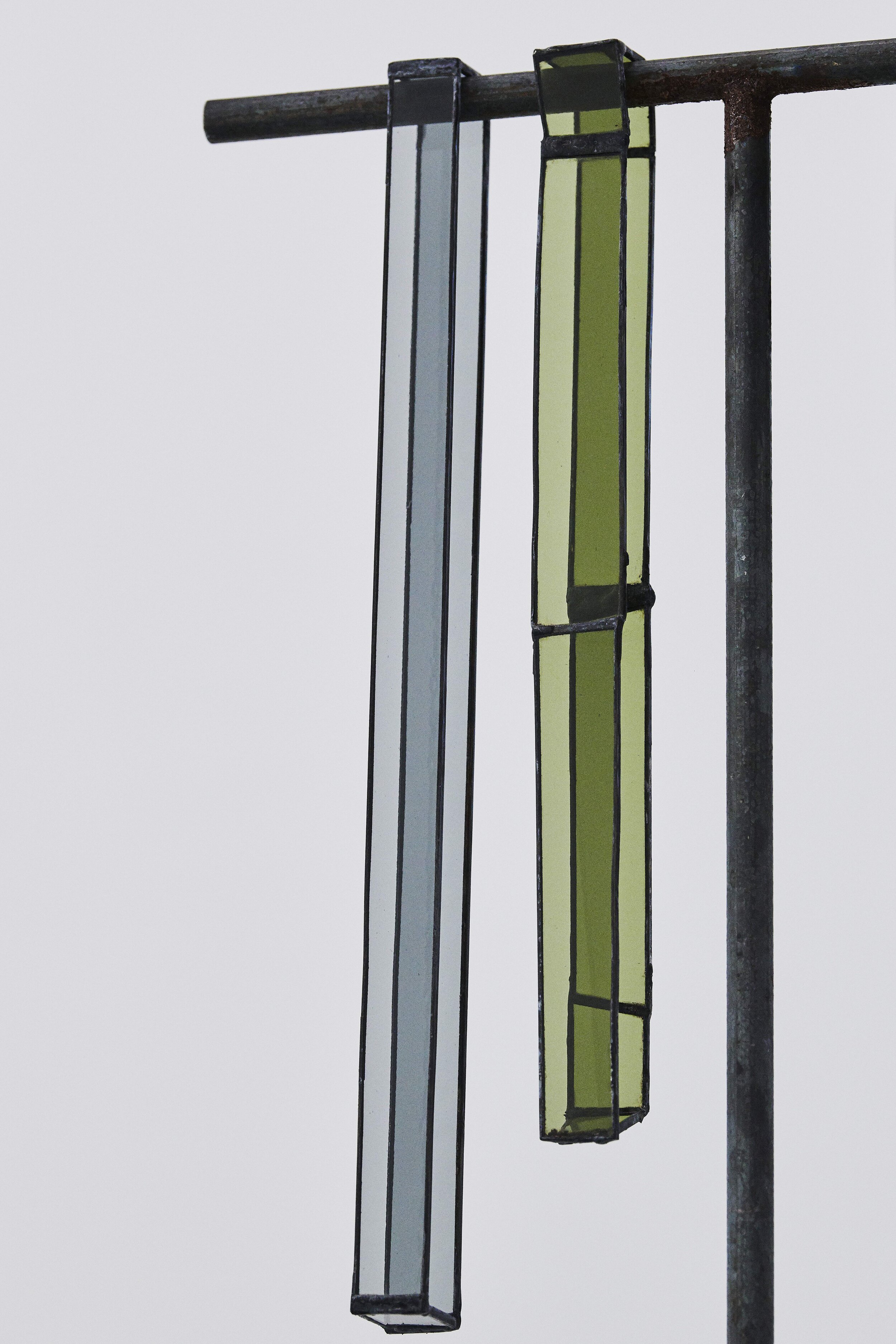

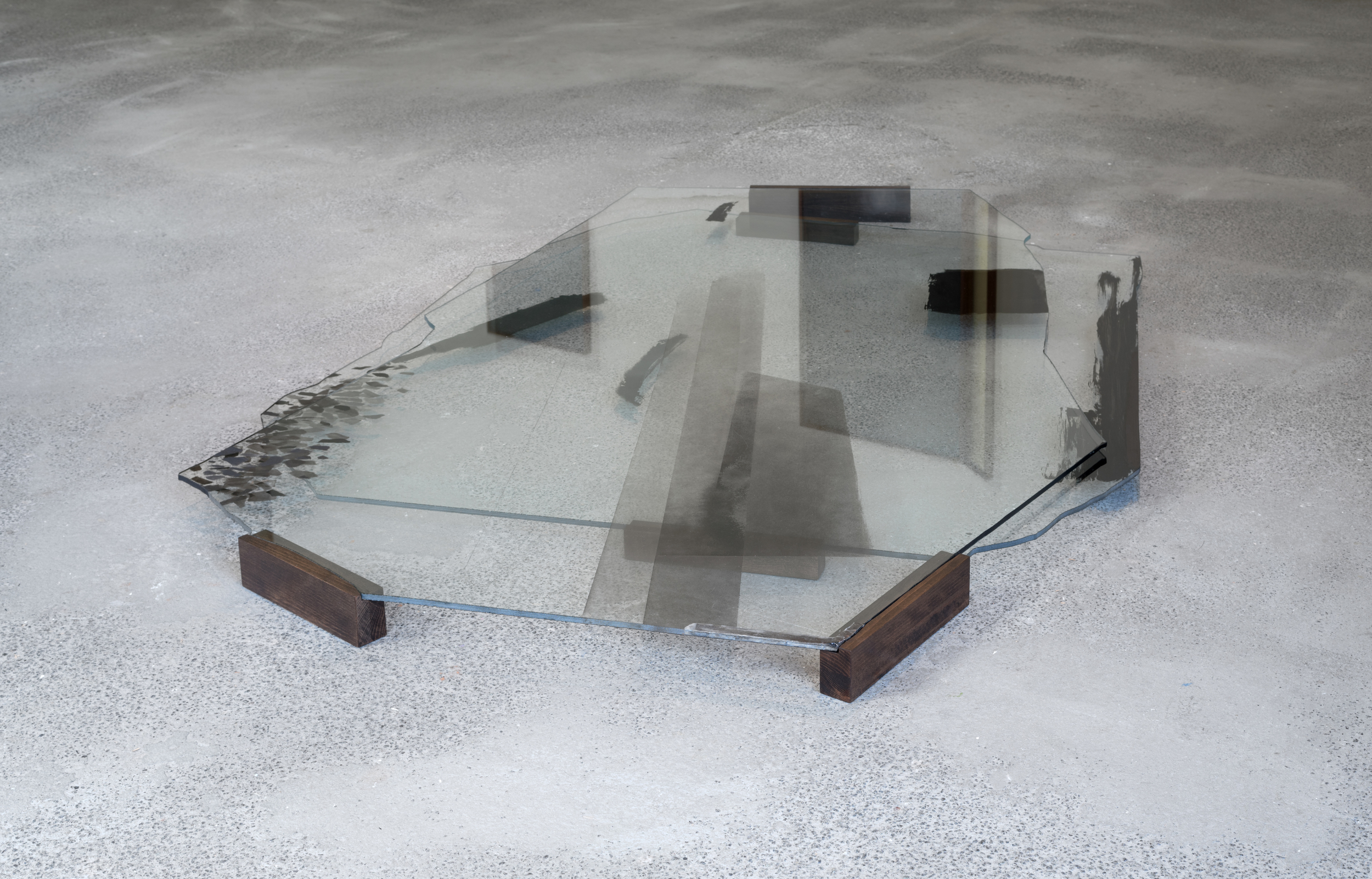

We, Finola Jones and (‘I’ – ghost writer) first became aware of Niamh O’Malley and her work, as a placeholder in absentia, some years ago while on a ‘scholarship’ (residency) at the British School at Rome, similarly by reported, narratised experience. Our home for three months was to be a large, open and bright room, formerly a marble-carving studio, in the simple Edwin Lutyens’ cloister beyond it’s deceptively grand façade (itself a surrogate, homage, pastiche, of the lower section of Christopher Wren’s St Paul’s Cathedral) [ii], facing out to the top end of the Borghese Gardens – and a placeholder in multiple movies. The all-white space concluded in large frosted-out window that, if ‘it’ could look out, looked out to nowhere in particular; a narrow lane and shallow car park beyond. Rather ‘it’ (the window) had been sadly reduced to a mute light box. Getting to know the institute’s staff and other resident ‘scholars’, we quickly established that the previous occupant of our studio remained more vividly in the collective imagination than we were likely to pull-off. She had held her place. As also ‘Irish’ scholars, we were evidently her (re-)place(ment)holder, and the work that had last been made and seen in ‘our’ studio, was firmly cemented in the perpetuated imagination of the staff and fellows – no mean feat for those pejoratively invested in the art of the long dead ‘ancients’. It seems that for the vaunted summer Mostra, Niamh O’Malley had meticulously painted an absent(entia) garden onto our blank backlit window panes. It’s a pity the garden left… (for whatever reason), yet glass, space, light, clarity, transparency, opacity, obfuscation and a conceptual vs. empirical exploration of ‘landscape’; nature and human symbiosis have remained core constituents within O’Malley’s practice.

In her essay accompanying Niamh O’Malley’s 2014-15, Douglas Hyde Gallery exhibition, Rebecca O’Dwyer compares the experience of the artist’s work and its oblique remove, to scenes from Ingmar Berman’s 1957, pertinently black and white, Wild Strawberries, where an aging professor, “…disillusioned and somewhat misanthropic…”, while travelling through landscape to receive a life-long career award, slips into a series of hallucinogenic reveries. The ‘real’ subsides into other, disjointed or distracted versions of itself [iii]. Exemplified in O’Malley’s agonisingly near-perfect work, and accordingly iconic work, Nephin, (2014), the concretisation of memory is collapsed by her deployment of the simplest of strategies, a ‘blind spot’. The eponymous 2,400 ft high mountain prominent to her native Mayo is deconstructed, dematerialised, while simultaneously maintained as the sole focus of view, of intent and the ineluctably singular object of memory: The artist and driver navigate bumpy roads around base of Nephin’s edifice, roughly targeting and overlaying a perfect, but imperfectly positioned, floating black dot mounted onto glass in front of a camera lens, and consequently disturbed and rattled by the unevenness of the roads and driven tracks, while all along, manually aimed at the mountain’s summit. Almost nothing, a distantly unachievable mountain, is rendered as the obsessive object of a fetishised gaze, filmed in near-Hitchcockian terse, tense, black and white.

In a more recent essay, Isobel Harbison invokes Maurice Blanchot to O’Malley’s cause; ‘But what happens when what you see, even though from a distance, seems to touch you with a grasping contact, when the matter of seeing is a contact at distance’ [iv]. Distance as a melancholic metaphor for potential objectivity, (the closer you get yet the further it seems to float beyond our grasp), facilitates the role of neutral and deflecting placeholder in O’Malley’s work. Objectivity by proxy? In Alice Through the Looking Glass, the White King asks Alice if she has passed Hatta or Haigha (his two servants; “one to fetch and one to carry”) on the road, but she declares that she has seen nobody. The White King expresses amazement, “I only wish I has such eyes… to see Nobody” and at such distance… admitting that he has difficulty seeing real people. Seeing, collecting, recording and processing the real, incidental details of the world around us obsesses O’Malley, feeling the pricks, the failures in the man-made blanket that increasingly envelops the natural world around us, with almost the same tangential, oblique weariness evident in the distracted manner of the White King. In an email O’Malley writes, that she has spotted an area of paving or a doorstep of sorts in the street outside a Dublin store, and she has become somewhat troubled by it. A pattern of regular grooves has been incised into an ancient and fossil-dense limestone slab. She writes that it’s hard to believe, to comprehend, the act of violence inflicted on such an ancient piece of the earth, merely so that we do not lose our grip, our footing upon it. It is in ‘its’ place so that we do not lose ours.

Of things in their place; the other day I had an extraordinary plane trip, nothing extraordinary in itself, a regular commute, but the seat behind me was occupied by someone who spoke consistently (to two complete strangers) from the moment of taxi and take off to the point of disembarkation. Rather than an annoyance it was something very special. Beginning at ‘A’, for avionics, and without noticeable pause thence on, he proceeded to commentate upon and explain the place held in the world of absolutely-every-aspect-of-everything, in alphabetical order. Getting to ‘P’, he suggested that; “you of course understand that [P]oetry occupies the space between [L]iterature and [M]usic”. Taking this as a purely brilliant determination and therefore the placeholder of unassailable truth, it occurred to me that this is how Niamh O’Malley understands the relationship of her art with the natural world, it’s a placeholder, a sound, in the space between fact and fiction, investigation and resolution, seeing and knowing.

I see no Spanish ships,

for there are no Spanish ships at sea.

[i] Webster.

[ii] Originally designed and constructed in 1911 for the International Exhibition of art in Rome

[iii] O’Dwyer, Rebecca, A Re-Thinking of Place, in; ‘Niamh O’Malley, The Douglas Hyde Gallery’, 2014. Pg.11

[iv] Harbison, Isobel, citing; Blancot, M. (1998) ‘The Gaze of Opheus’ in Quasha, G (ed.) The Station Hill Blanchot Reader, Station Hill Press, NY. Pg 413, in: Of saving, of hoarding, of keeping to hand, in ‘Niamh O’Malley’ the Royal Hibernian Academy / John Hansard Gallery Publ. 2019. Pg. 63

Images Courtesy mother’s tankstation limited